- Home

- Su Bristow

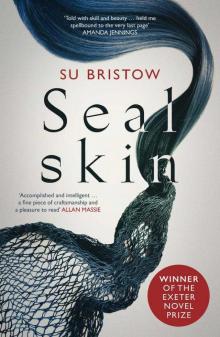

Sealskin

Sealskin Read online

Praise for Sealskin

‘Sealskin is an accomplished and intelligent novel, a fine piece of craftsmanship and a pleasure to read’ Allan Massie

‘Bristow has taken a known myth, and created an enthralling, human love story. A profound achievement, and a stunning debut’ Richard Bean

‘An extraordinary book: original, vivid, tender and atmospheric. Su Bristow’s writing is fluid and flawless, and this is a story so deeply immersive that you emerge at the end, gasping for air’ Iona Grey

‘I love books in which magic takes on a gritty reality, and Sealskin is just such a book. Dark and brooding and half-familiar, the tale steals over you till you're half-in, half-out of a dream’ Jane Johnson

‘An evocative story, told with skill and beauty, that held me spellbound until the very last page’ Amanda Jennings

‘On the face of it, Sealskin is a gentle tale, a lovely reworking of the selkie legend many of us have known and loved since childhood. Do not be fooled, dear reader; beneath this simple re-imagining lies a story as deep as the ocean the selkie comes from. I was captivated from the first page to the poignant last one, by the sympathetically drawn characters and a mesmerising sense of place. In between are moments of tragedy, moments of grace and redemption; the whole wrapped in Su Bristow’s charismatic writing. This is a story that catches on the edge of your heart, leaving tiny scars; reminders of a journey into a beloved legend, the human lives caught up in it and the consequences of the choices they make. It is, quite simply, exceptional’ Carole Lovekin

‘In this achingly beautiful retelling of the classic Scottish folk tale, Su Bristow brings psychological depth and great warmth to the characters, making the ending all the more heart-breaking. It's a story about the tensions of life in a tiny fishing community, about bullying and violence as well as the healing magic of nature. It's written smoothly and skilfully with not a word too many or a word too few. I absolutely loved it and can't recommend it highly enough’ Gill Paul

‘A beautiful and bewitching read that haunted my thoughts for days. The sense of the sea, of this small community, of guilt is palpable. This is one of those books you place reverentially on your bookcase and envy those who are yet to dive in’ Michael J. Malone

‘Sealskin is the most exquisite tale of love, forgiveness and magic. Inspired by the legends of the selkies, this gorgeous novel is a dark fairy tale, an ode to traditional storytelling, a tribute to the stories we loved hearing as children. But be warned – this is no happy-ever-after tale. The language is just glorious, poetic and rich but precise. And her characters – oh, they will remain in your heart long after you’ve closed the last page. Mairhi – especially since she never really “speaks” – is a beautiful mystery, but one who haunted me when I was between chapters. If this is her first, then I can’t wait to read whatever Su Bristow bestows upon the literary world next’ Louise Beech

‘Ms Bristow’s skill in weaving a centuries-old tale into a current-day fiction novel and binding the two together is simply superbly done. Sealskin is boldly written, brilliantly told and a tale of legendary proportions’ JM Hewitt

‘Sealskin is a magical and moral tale woven with a deft hand’ Sara MacDonald

‘With its beautiful language and magical storytelling, Sealskin is a clear winner for me’ Sophie Duffy

‘Sealskin is exquisitely written with haunting prose and evocative descriptions of the Scottish landscape. It's filled with beauty, surprises and subtle twists and turns. There's a mesmerising love story at its heart. I really didn't want the story to end, and felt bereft when it did, surrounded by boxes of tissues. I'm sure I'll be reading this book several times to feel that magic again and again. It's no surprise that Su Bristow is an Exeter Novel Prize winner. Her writing is beautiful and this book is stunning. Sealskin is destined to go far’

Off-the-Shelf Books

‘Sealskin really is one of the most beautifully written books I've ever read … a flowing tale of love, friendship, acceptance and coming of age for the varying characters. Set against the ruggedly beautiful Scottish backdrop, the vivid descriptions draw us in, detail oozing from the pages and giving the reader a chance to feel the coastal winds whipping at their faces, taste the salt in the air, feel the uneven terrain underfoot as they clamber through the heather and over rocks. There's a magic in these pages … poetic and hauntingly beautiful’ The Quiet Knitter

‘A compelling and beautifully written book. At one level Sealskin is a delightful re-working of the selkie myth. But it is also a great deal more than that … The fishing village is a close knit community wary of incomers, the suspicion with which they greet Maihri is typical of how they behave. Strangers, especially ones who are a little out of the ordinary, are not made entirely welcome. It is a story of how relationships develop and grow. Sealskin is a quite delightful and extraordinarily well-written book. Highly recommended’ Trip Fiction

‘A sensuous and beautifully written retelling of the Selkie legend which captivated me’ Margaret James, Creative Writing Matters

’I knew this was special, right from the first paragraph. A beautiful book written with a deceptive simplicity. But Su Bristow does not shy away from asking some very big questions. How can a man atone for violence? Will he ever be forgiven? Will he ever forgive himself? Utterly spellbinding’ Cathie Hartigan

Sealskin

SU BRISTOW

For Moraig MacLauchlan,

my mother,

who never found her way back

SEALSKIN

CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

THE LEGEND

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

1

‘You can’t trust moonlight.’ His mother set the lantern down. She hesitated, and Donald guessed what was coming.

‘It’ll be a grand night for fishing, with the full moon,’ she said, looking away. ‘Your Uncle Hugh came by this morning, and he says they’ll be out overnight. They could do with your help on the boat.’

‘They’ll manage.’ He moved towards the door, but she stood her ground, looking up at him, and he could not push her aside.

‘Callum’s not well. They’re a man down, Donald.’

That made him pause. Callum Campbell was the worst of them. His uncle said it was only banter, but the sting of it stayed with him, sometimes, longer than cuts and bruises; and there had been enough of those, too, in the schoolyard and i

n other places where there were no adults to see. Maybe it wouldn’t be so bad if Callum wasn’t there.

His mother saw the change in him. ‘Hugh asked for you specially. You know, none of them thinks the less of you because of your hands. Here, let me see now. Wait while I fetch the salve for you.’

But now she had said too much, pushed him too far. What could she know, anyway? Women never set foot on the seagoing boats; it was bad luck. And nearly as bad luck to take a man whose hands cracked and bled on the ropes, who could barely hold a knife by the end of the night. Much better to make his own way, out of sight of their pity and their scorn.

He pulled his hands away, and shouldered the empty creels, making a barrier between himself and his mother. ‘Leave it. They’ll be fine. I’m more hindrance than help, and Uncle Hugh knows it.’

‘Oh, Donald. A night like this, you shouldn’t be out alone. Go with Hugh, just the once?’ She was almost pleading with him; but now he only wanted to be off, away.

‘I need to see to the crab pots. Anyway, it’s too late to go with them now. They’ll want to catch the tide.’ Armoured with his burdens, he made his way to the door, and after a moment, she came to open it for him.

He went out into the moonlit garden. His mother stayed in the open doorway, watching him out of sight, but he did not look back.

Picking his way down the path to the shore, on his own at last, he began to feel easier. A night like this! Where else would he be but alone? Cooped up on the boat with the others, there’d have been no time to look, to listen, to breathe it all in; but out here, with the vastness of sky and sea all to himself, a man might witness marvels. There was not a whisper of wind tonight, and no sound from the sea at all. As he walked along the strand to where his rowboat was drawn up, the waves were lapping at his boots, just stroking the shoreline, hushing it like a woman soothing her child.

The boat was silvered all over with tiny frost-flowers, sparkling in the moonlight. Donald paused, unwilling to lay hands on it, to spoil its perfection, to mar the utter stillness of the night by dragging it over the shingle and rowing out from the shore. Almost, at times like this, he could love the sea. But there were jobs that had to be done, and the tide was turning. He bent to the task.

2

Donald heaved again at the sodden, barnacle-crusted rope, hissed at the pain in his cracked hands and hauled the crab pot aboard. Cold water washed over his feet, but along with the sea wrack that somehow always got into the pots along with the crabs, there was movement. Hard to tell how many, in the shifting moonlight. He reached in, feeling past the slimy strands of weed for flat shells, crawling legs, and lifted out the first catch, its claws waving uselessly as he dropped it into a clean creel.

He was right in the moon’s path, as clear as a straight road to the Land of Youth on this calm, windless night. Where the souls of the dead go, the fishermen said – not in church, of course, but in the bar on stormy nights when the boats were still out; there to drink mead and take their ease in the gentle fields rich with barley. Donald, flexing his sore and frozen fingers, doubted the truth of it. Drowned fishermen stay down, he thought; his father and all the rest who’d ever put out from this coast and not come home. Crabmeat, and anchorage for limpets and anemones, that’s what they became. Pulling again on the rope, he moved on to the next pot.

There were seals on the skerry tonight, no more than fifty yards of black water and hidden rocks away, on the little strand that was only clear when the tide was low. They looked as though they were basking in the moonlight, though it was far too chill for that. As he watched, a couple more dragged themselves up from the sea, heavy and awkward, moving slowly up the sand. They were rolling, heads swaying to and fro, buffeting each other as they moved clumsily forward.

Moonlight silvered everything, casting doubt and shadow. So he scrubbed at his eyes and looked again, but they were still rolling, rising up, standing and stepping out of their heavy skins, helping each other to get free. Six, seven, maybe nine young women, lithe and graceful, holding hands, beginning to sway and dance as though the moon had pulled them up and out of the sea, almost airborne, drunk with the joy of it.

Drifting silently by the rocks, he stared. All of them were up now, leaving their sealskins like wet rocks on the sand, running and leaping, barefoot and naked, gasping with hoarse laughter as they chased each other along the beach. He could not stop staring. Another bar story: the seals who are also people, who come ashore from time to time in places no-one sees. But he was seeing; he was drinking with his eyes, as full of elation as they were. Maybe the Land of Youth was true, too, then; maybe all those wishful, drunken tales were true. But he could not spare a thought for them. Only this was true, and real, and now.

Almost without thinking, he had taken the oars and begun to move nearer, staying behind the rocks though it meant he lost sight of them for a time, and rowing with hardly a splash, the way he’d taught himself on all the long nights out fishing alone. Weaving between boulder and boulder, he found a place to step out and drag the boat ashore. They were still out of sight. Inch by inch, he made his careful way onto the strand, hearing the creak of his boots and the shift of stones under them. But, after all, the beach was empty.

He only realised he was holding his breath when he took in the pile of skins, still lying where they had been shed, and let it all out in one great whoosh. His eyes had not been playing tricks on him; this was real. No sign of life; though now, as he listened through the thudding of his own heart, he could hear laughter some way off. As cautious as a hunter, he crept towards the skins, crouching low, watching for movement. There was none. They lay, mottled and glistening in the moonlight, abandoned.

He put out a hand and touched the nearest. It was warm, as though some of its owner’s life still lingered in it. Bolder now, he pulled it towards him, running his hand along the grain of the smooth pelt. You could never get close enough to touch a seal, unless it were dead or caught in a net, but the skins were useful to keep out the cold. And who knew what magic these might hold. Surely, this was a gift, just for him. Glancing around, he lifted it and pushed it between two of the rocks. He could come back for it later; right now, his mind was elsewhere.

They had moved off between the birches and rowans that grew above the tideline, into the places where the thick, unwieldy body of a seal could never go. They were picking rowan berries, eating them and spitting out pips, hanging the bunches over each other’s ears, picking leaves and running them over their breasts and thighs. Those heavy pelts must keep out most sensations, he thought. They looked like children fresh from the bath, more naked than naked, like the white inner twigs of fir when the bark is stripped off. He had never seen a girl without her clothes, did not even know if these would pass for human; but his body at least was in no doubt. He stood there, rigid, the blood roaring in his ears, and wanted to weep for the glory of it.

And then one of them saw him.

She gave a sharp cry of alarm, almost a bark, and all their eyes were on him. The next moment they were streaming past, leaping and slipping on the hidden boulders, as he stood there with his arms outstretched, hoping somehow to hold them back. They jostled him as they fled, and he stumbled after them back down to the beach, where they were already melting down into their skins and heaving themselves towards the water, all grace gone. As he reached the water’s edge, the last one slid off the rocks and was received into the gentle, swirling waves.

Donald stood there, exultant and desolate all at once. He could see their heads turning to look at him, but he knew they would not return. He watched for a few moments longer, seeing in his mind’s eye their glorious, dancing forms. Then a small noise to his right made him glance up, and freeze.

3

There was one left. She was pacing along the edge of the waves, wringing her hands, uttering little short cries as she yearned towards the dark water. The heads of her sisters gleamed as they waited for her some yards off.

Donald understood in

a moment what had happened. He started forward, hands held out, and she backed away, her eyes wide. A few more steps and she would stumble into the rocks where her skin lay hidden. He broke into a run and was upon her almost at once. She seemed weightless, slight as a child, and they fell together on the hard, ribbed sand.

She writhed like an eel under him, but he held on tightly, feeling her breasts crushed against his chest, one leg between her thighs. For a moment her black eyes stared straight into his, and there came a great rush of terror – the fisherman’s last grasp at life as the hungry sea swallows him – and the stink of drowned things was in his nostrils. He closed his eyes and hung on. Then her defence was down. She cried out once as he entered her, and after that made no sound at all.

When he came to himself again and looked around, there were no more bobbing heads in the water. She lay still, her head turned away, but as soon as he began to get up she twisted aside and tried to run. Grabbing her wrist, he pulled her up and towed her towards his boat, avoiding the place where he had concealed the skin.

Once in the boat, he rowed hard for the shore. He was afraid at first that she might jump into the water, but it seemed that, although she stared across the gleaming waves and reached out to her sisters, she could not join them.

Soon they came safely to land, and now he took thought and stripped off his shirt. He tried to get her to put her arms into the sleeves, then gave up and wrapped it around her, and so they came stumbling through the darkness, up to the cottage, where his mother had placed a light at the window to guide him home.

He pushed open the door and she was there, seated by the fire, stirring something in the big pot.

At once, he began to talk. ‘Look what the sea cast up; there must have been a wreck, I think. I found her like this, down on the shore. She doesn’t speak; it’ll be the shock, maybe. Have you something to clothe her with?’

Sealskin

Sealskin